As a young agriculture economist, I dreamed of working on beer, wine, or weed. Not because these topics lead to prestigious research or academic glory, but because sitting at a winery drinking wine and dubbing it “research” IS the dream.

That’s partly how I ended up sipping English sparkling wine (which no one would’ve believed existed 20 years ago), surrounded by 80 researchers at a wine symposium in Oxford.

But the dream turned dark when another attendee uttered the dreaded word: degrowth.

The climate is changing and vineyards are water-intensive. Where the Pinot grapes grow now, they won’t be able to withstand an increase in temperature. Maybe we shouldn’t grow Pinot Noir. Maybe it is not the best use of the land. Savor this today, for who knows about tomorrow?

I sat listening to the conversation, aghast. So much pessimism around a grape that is synonymous with weddings, graduations, parties: the party grape.

Amidst this lamenting and loss, an ag economist from UC Davis piped up: “Actually… we already have drought-resistant varietals. Genetically very similar to Pinot. There are no acres planted.”

I waited for a collective sigh of relief, a hoorah. The day is saved! Nothing. And that’s when I realized: the problem isn’t the science. It’s everything else: wine culture is tradition-bound; planting new grape varietals is risky; consumers have been trained to recognize a handful of products.

And yet, you can find major acts of adaptation in the recent history of winemaking. We can do it again if we have to–and we probably will have to.

Monks and the Makings of a Market

While grapes have been cultivated for millennia, it wasn’t until the 11th and 12th centuries that wine makers began to take a more structured approach. Monastic orders began acquiring and cultivating vineyards across the Côte d’Or in Burgundy. These monks kept some of the first records, noting that different vineyard plots produced different flavors, giving rise to the concept of terroir, the idea that place shapes taste.

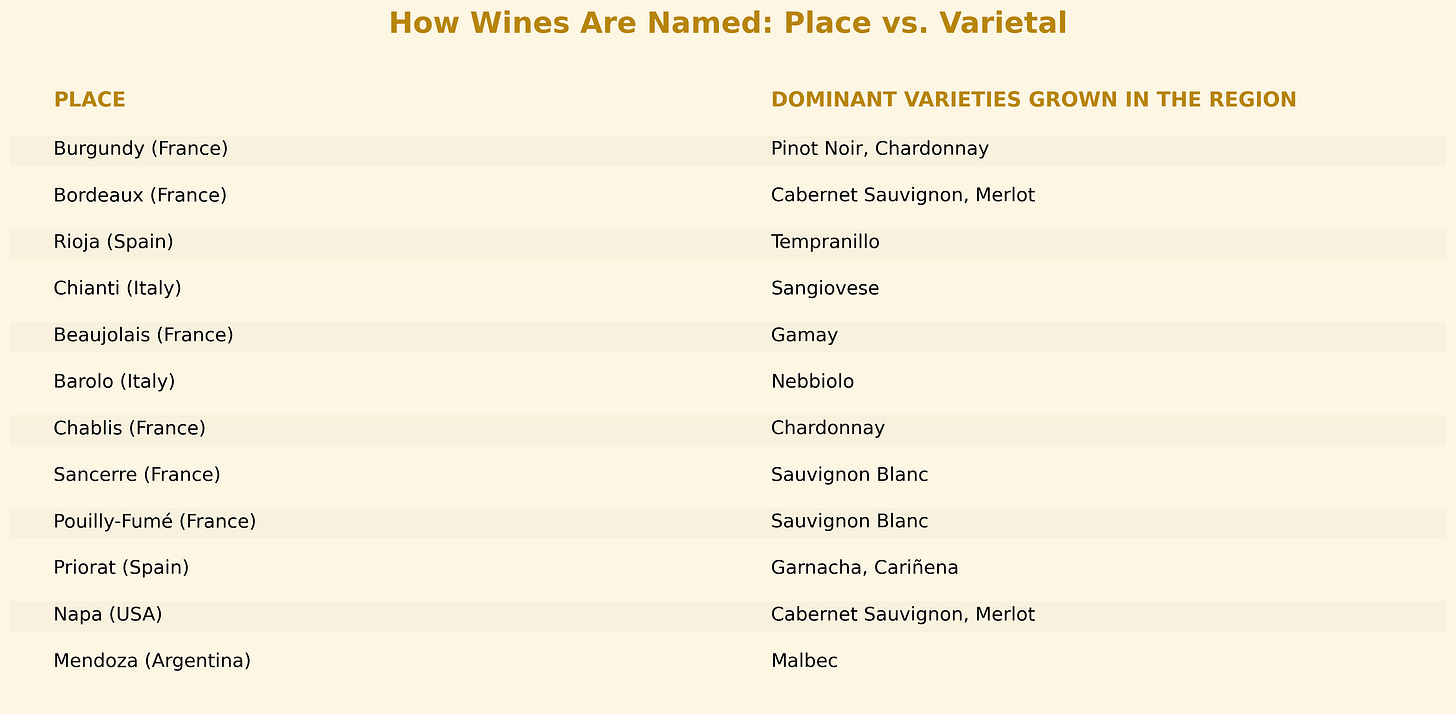

At this time, wines were sold by region, a tradition that persists to this day. The first mention of a grape varietal (think Malbec, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir) is when Philip the Bold decried the planting of Gamay (a cousin of Pinot Noir), claiming it was a ‘very bad and disloyal plant.’ This documented casting out of Gamay and exaltation of Pinot Noir marks a shift towards marketing wine by variety.

The Birth of Bureaucracy

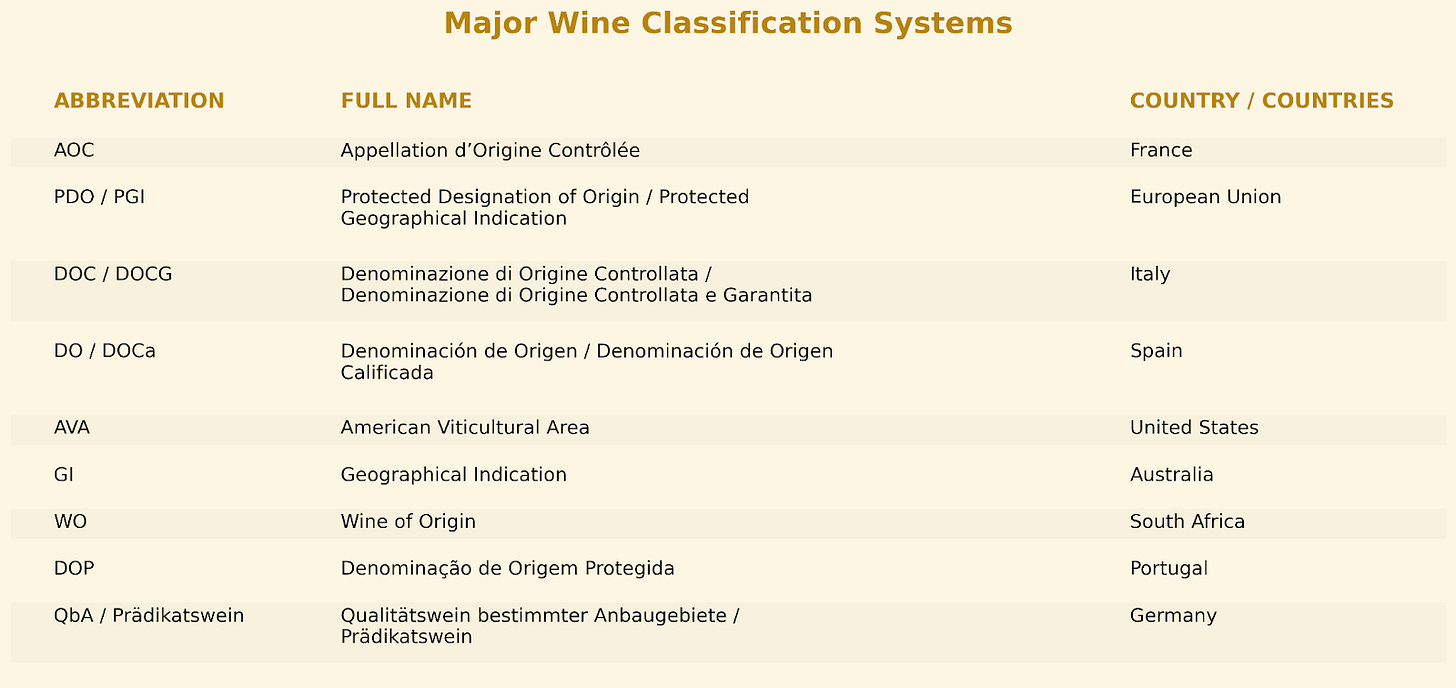

While Philip the Bold’s proclamation marked an interest in varietals, geography continued to dominate for the next several centuries in the marketing of wine. Regions like “Barolo” or “Burgundy” spoke as signals to consumers, demarking wine characteristics and quality. This logic would eventually formalize into modern appellation systems like France’s Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) or Italy’s Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC).

The AOC (France) and DOC (Italy) create tight controls. They dictate which grapes may be grown, how much can be harvested, and under what conditions. When someone at a party tells you, “It is sparkling, not champagne,” that’s the AOC at work!

The U.S. possesses a much more lax set of rules (my colleague, Clint Neill, and I have forthcoming work examining how these institutional structures have shaped Pinot Noir’s identity, see conference abstract here) called American Viticultural Areas (AVA). AVAs represent geographically defined growing areas but have far fewer rules. A bottle only needs to have grapes grown 85% in a designated AVA for it to be labeled as such.

All of these systems aim to protect tradition and signal quality to consumers. And to some degree, they do. They also often draw arbitrary boundaries. The nuance within an appellation can be immense. Grapes and their resulting flavors/quality can vary based on slope, soil composition, and sun exposure. The label designated by the AOC, DOC, etc. flattens that into a single name. AOC and DOC maps are drawn by people, not by nature. In some cases, these boundaries were shaped by political influences or marketing moves, rather than reflecting the terroir.

Here’s the catch: wine is obsessed with provenance. That fixation has kept new grapes on the sidelines, until phylloxera tore through vineyards and forced growers to graft, clone, and scramble for survival.

The rise of the clones and the Phylloxera panic

Alongside evolutions in legal definitions and institutions, grape breeding evolved. As Europe colonized other parts of the world, “old world” varietals spread to new wine-growing regions (think the United States, Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Chile). In these locations, new “clones” began to appear. Grapes are hermaphrodites, meaning their flowers are capable of self-pollination. Practically speaking, this means stable varieties are created through cuttings. Each cutting is a genetic clone of the parent plant, which is why a Pinot Noir clone in the Willamette Valley of Oregon can have its origins in Burgundy.

Understanding clonal propagation enabled winemakers around the world to begin to select for traits such a flavor profile and yield suited to their tastes and the local area.

As clones were making their way to the “new world,” the “new world” was sending back its own gift. In the 19th century, an itty-bitty insect, phylloxera, changed vineyards in Europe forever.

Phylloxera comes from North America, where native grape species had centuries to toughen up against it with thicker root bark and other defenses. But European vines never faced the bug, so when it hit Europe in the 1800s, they were sitting ducks. By the end of the 1800s, it is estimated that nearly two-thirds of France’s vineyards had been destroyed. Phylloxera ravaged Europe, spreading to other prolific wine regions such as Spain, Germany, and Italy.

In the late 1800s, Charles V. Riley (American entomologist) and Jules Émile Planchon (French botanist), saved the day by discovering that European vines could be grafted to American rootstock. Today, nearly 90% of vines are grafted in this manner, and phylloxera continues to be considered endemic throughout the world. European varieties were saved by splicing old-world genetics with new-world rootstock.

While grafting is a common practice today, it was novel and disruptive at the time. Since then, vineyard managers have grown increasingly conservative when it comes to introducing novelty into the vineyard.

The Climate is Changing. The Vines… Aren’t.

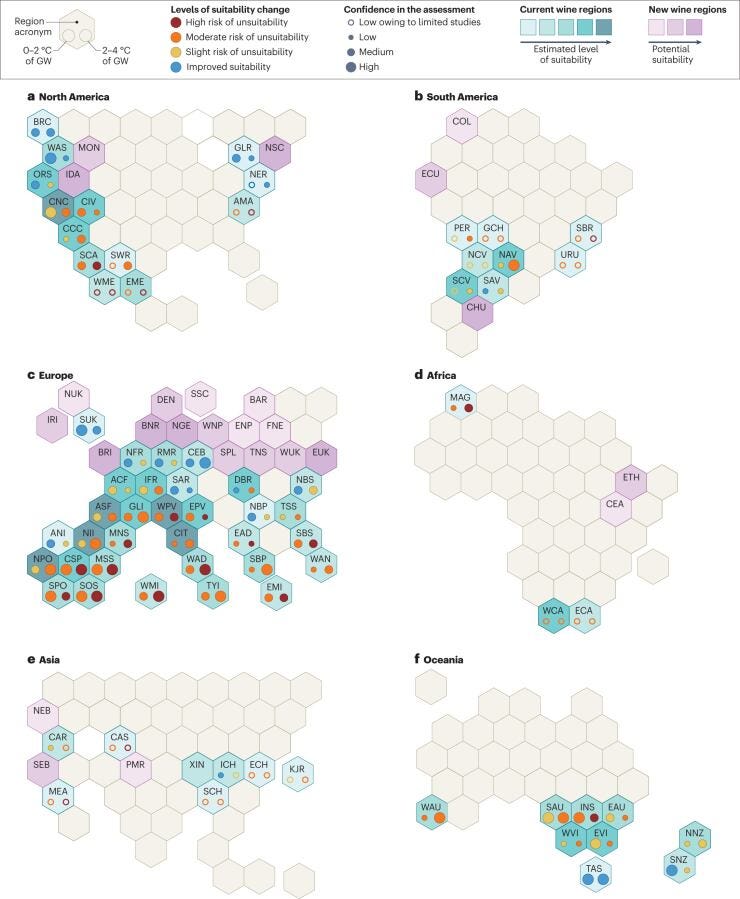

If you are in a room full of folks passionate about wine, inevitably the fight against phylloxera will be brought up and hailed as one of the greatest global efforts in modern agriculture. The warming of our planet threatens a widespread decimation of vineyards on the scale of phylloxera.

It's been warned that if temperatures rise more than 2℃, up to 70% of today’s winegrowing regions could become unsuitable for the grapes that are currently planted. On the flip side, warming could make about 25% of today’s winegrowing regions more climatically favorable, and as many as 26 new wine growing regions could emerge.

But this optimism deserves a reality check. These projections focus on climate. Vineyards don’t materialize because the weather shifts. They require decades of patient investment and careful design.

Remember that glass of English sparkling I mentioned? That vineyard wasn’t the product of a single warm season. It took nearly a decade of site visits, soil testing, slope analysis, and microclimate mapping before a single vine was planted. That vineyard was a decade in the making, with hundreds of site visits, thousands of soil tests, advanced GIS mapping to understand the microclimate, water runoff, slope, and a thousand other factors. Climate might set the stage, but terroir, time, and capital also determine whether a vineyard can exist at all.

These projections make one thing clear: new grapes are necessary. Thankfully, we have them. Scientists all over the world have been anticipating and responding to the trend of the Earth getting hotter. The problem is that no one is planting these vines.

Faux “Franken-vines”

Ever heard of a Frontenac? Drank a Marquette? Tasted an Artaban? You aren’t alone.

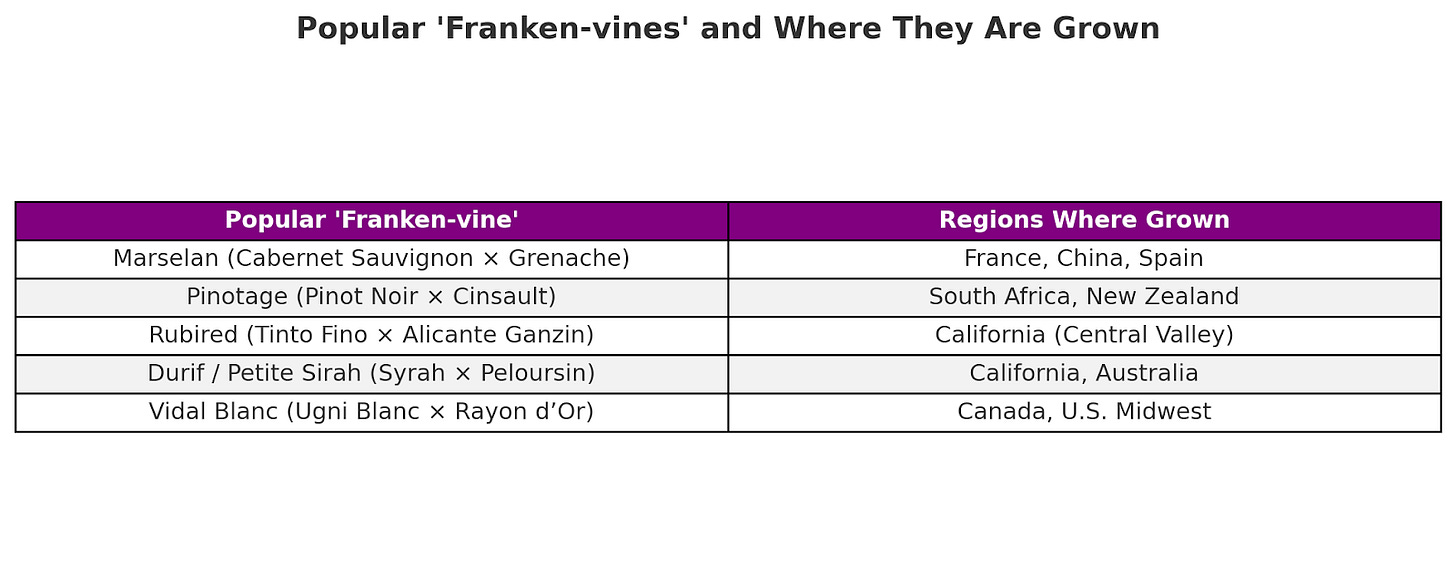

Dozens of grape varieties bred to be resistant to problems like fungus or be less water intensive are currently planted in limited or near-zero quantities. Researchers from institutions like UC Davis, European Pilzwiderstandsfähige (PiWi), and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) have bred more eco-conscious grapes that thrive with fewer pesticides, less water, and are resistant to known diseases.

These grapes are built for the here and now, biologically and politically. In order to comply with European Union rules on genetically modified organisms, these varieties are the result of intensive breeding crosses rather than genetic modification. Some of these hardier vines are up to 98% genetically identical with classic varietals such as Pinot Noir. These varieties are not “genetically modified organisms” (GMOs). Although rigorous side-by-side studies remain scarce, anecdotal results from blind tastings indicate that hybrid wines often stand on equal footing with their traditional counterparts.

Despite being the result of conventional breeding programs, many still consider them “Franken-vines.” Which brings us to the wine industry’s culture problem.

The Bottlenecks

While most of us probably don’t subscribe to The World of Fine Wine or book a flight when Jancis Robinson declares the new MUST TRY boutique winemaker, the wine elite continue to drive the market in subtle (and not so subtle) ways. They curate restaurant wine lists, set industry benchmarks, and write the reviews that distributors and retailers follow. They canonize certain grapes while treating others as curiosities at best and abominations at worst. And above all, they cling to tradition. Tradition may be beautiful, but it can also impede progress and adaptation.

And then there’s everyone else. The majority of wine drinkers aren’t collectors or sommeliers. Most wine drinkers are just looking for something enjoyable to drink with dinner. This group doesn’t obsess over vineyard elevation or soil pH. They pick bottles based on labels, price, or a vague memory of liking Malbec that one time. This group still inadvertently adheres to tradition. The store shelf is still organized by varietal. The language on the label still emphasizes “classic” grapes. Hybrid wines are lost in a sea of labels. If it doesn’t say Chardonnay, Cabernet, or Pinot, most people don’t pick it up.

On the other side of the equation, producers are dealing with sunk costs and brand identity. Vineyards don’t replant every year. Vines live for decades, and new plantings take time to mature. Gambling on a new variety with an unknown grape could put a vineyard in the red in a business that already operates on thin margins.

Mix that all into a set of regulatory institutions that are inflexible, and you’ve got a long road to adoption.

Institutions: Aging Poorly

The institutions surrounding wine (AVAs, AOCs, DOCs, PDOs, etc.) were designed to protect tradition, not foster innovation. In a way, they’re working exactly as intended. And that’s the problem.

The EU legalized hybrid grapes in 2022 through the PDO system. Hypothetically, this means growing hybrid grapes in EU countries is legal. In practice, regions have been left to make their own decisions on whether or not hybrid varieties are allowed.

For example, France’s national wine authority, the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (INAO), approved a couple of disease-resistant varieties, such as Floreal and Vidoc, for national use. However, for them to appear in AOC wines (wines having a label that states it was grown in that AOC), the individual appellations must approve them. Italy faces a similar problem. Wines developed by PiWi remain in an experimental category, and the use of hybrid grapes in AOC wines depends on individual appellations to approve.

While much of Europe is stuck with regulation that hinders experimentation, the United States has no regulatory structure to introduce or incentivize the adoption of new varieties. Essentially, the institutions that have been built around wine are meant for a world that no longer exists.

Final Pour

Wine has long been a story of adaptation. Monks discovered terroir, breeders selected for superior varieties for centuries, and grafting onto American rootstock saved European vineyards.

Wine is faced with another turning point. They have the tools to deal with it if they could learn to build upon tradition instead of sticking with tradition. Drought-resistant grapes and disease-tolerant hybrids exist. What is lacking is the incentives, institutions, and imagination to plant them.

Perhaps we could:

Subsidize the switch: Replanting a vineyard costs tens of thousands per acre. Offsetting grants from grower associations or replanting rebates would de-risk the choice for producers.

Reward experimentation: The wine industry has a long history with competitions like the Wine Olympics. Creating an arena for producers to showcase experimentation in front of industry elites could create prestige that wine producers strive for.

Loosen the varietal grip: Systems like AOC or PDO could widen what varieties are allowed, letting place still carry meaning, while welcoming new grapes adapted to new climates.

Re-center the region: Wine was marketed by place for centuries. Reverting to place as the primary way to market wine could allow a Savoie white to be special (even if it's only 80% Sauvignon).

Wine has adapted before. It can do it again. The only question is whether we’ll make the leap now, or toast to missed opportunities later.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Mike Riggs, Hiya Jain, Andrew Burleson, Étienne Fortier-Dubois, Tim Durham, and Smrithi Sunil for feedback and edits. If you haven’t already, you should check out the 2025 Roots of Progress Fellows!

Literature Cited

van Leeuwen, C., Sgubin, G., & Gambetta, G. A. (2024). Climate change impacts and adaptations of wine production. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00521-5