A Lab in the Litterbox

Inside the Wild West of At-Home Pet Diagnostics

At the end of October, I interviewed for a fellowship in animal health, more specifically, pet health. Lately, most of my attention has been on the welfare of food and large animals (cows, horses, hogs, sheep, goats, etc.). But in a previous life, I ran the Pet Ownership and Demographic Survey for the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA).

Back then, my days revolved around questions: How many pets do you have? Where did you get them? When was your last vet visit? The goal was simple. Help veterinarians understand trends in pet ownership so they can grow and sustain profitable practices. It was a blast. (Bird folks, you WILD. The dedication it takes to own an African Gray parrot continues to amaze me.)

I’ll be honest. While the majority of people claim to think of their animal as a family member, I don’t think the average person puts their golden doodle and toddler on equal footing. (Although Pennsylvania did introduce a bill this year to require courts to weigh different factors impacting the well-being of a pet during divorce, which feels like the legal system is inching toward “pet custody hearings.”) Still, as a millennial pet parent, I will admit that my dog eats a special GI diet and sees a specialist because he has IBD (just like me). I am the poster child for the rising amount of time and money that folks spend on their pets.

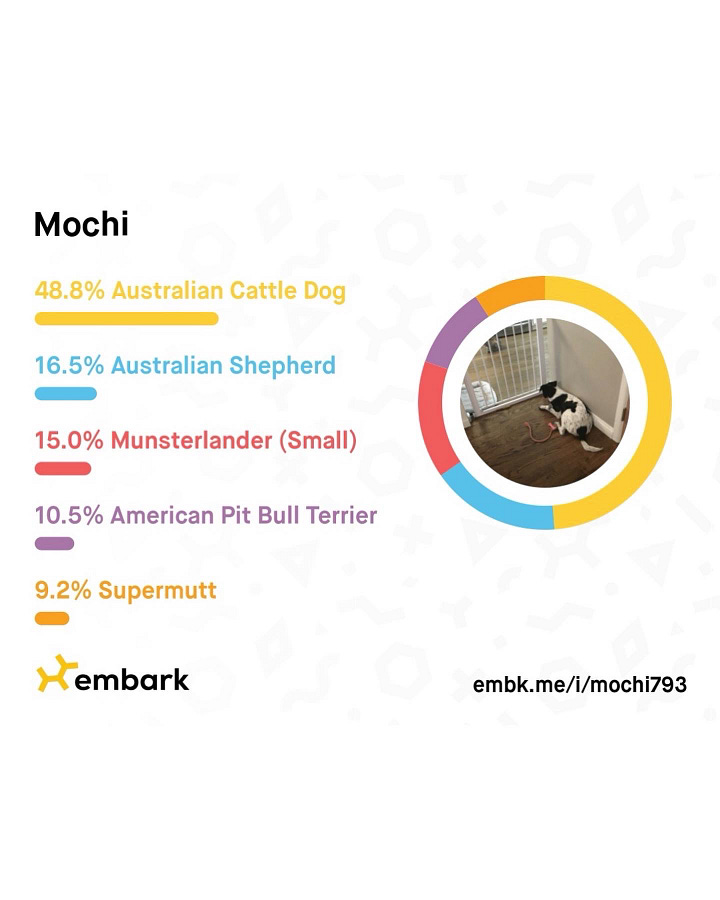

Preparing for this fellowship interview required submitting a short case study. I decided to write about something I knew embarrassingly little about: at-home diagnostic tests for pets. As the owners of a pack of rescue dogs, my husband and I have done our fair share of Embark Dog DNA tests. Spoiler: one ended up being a purebred Shiba Inu, and the other 100% pitbull. Disappointing from a frankendog perspective. We did have one end up being what I lovingly call a cow-bird-pitbull, so at least one of my pets managed to deliver on the intrigue front.

So I went in expecting to find a couple of dog genealogy tests, maybe a take-home kit your veterinarian could give you for those animals who have a hard time providing a fecal or urine sample under pressure. What I found was a rapidly burgeoning mini-market of take-home tests that were already on the shelves of Target, available on Amazon, and ready to go if you called 1-800-PetMeds! Some tests require you to mail a sample to a lab. Some were true rapid tests that you can run from the comfort of your home.

This wasn’t a novelty. It’s a rapidly growing segment of the market. And a segment that no one has really written much on. Today, I’m here to introduce you to the landscape of animal health at-home diagnostic tests (or more broadly, the device segment of the animal health market). It’s kind of weird, very Wild West on the regulation front, and I’m still working it out on what it all means.

In a previous post, I’ve alluded to what I find an interesting problem. Much like in humans, animals require a Veterinary-Client-Patient-Relationship (VCPR) with their veterinarian for treatment. Veterinarians take this VERY seriously, despite there being little evidence for what is “best practice” in terms of animal welfare in this relationship.

Which brings me back to the aisle of diagnostic tests. The majority of these tests exist outside of a veterinary clinic and are being marketed direct-to-consumer.

I suddenly had a new question.

WHO, EXACTLY, IS REGULATING ALL OF THIS?

What even counts as an “at-home” test?

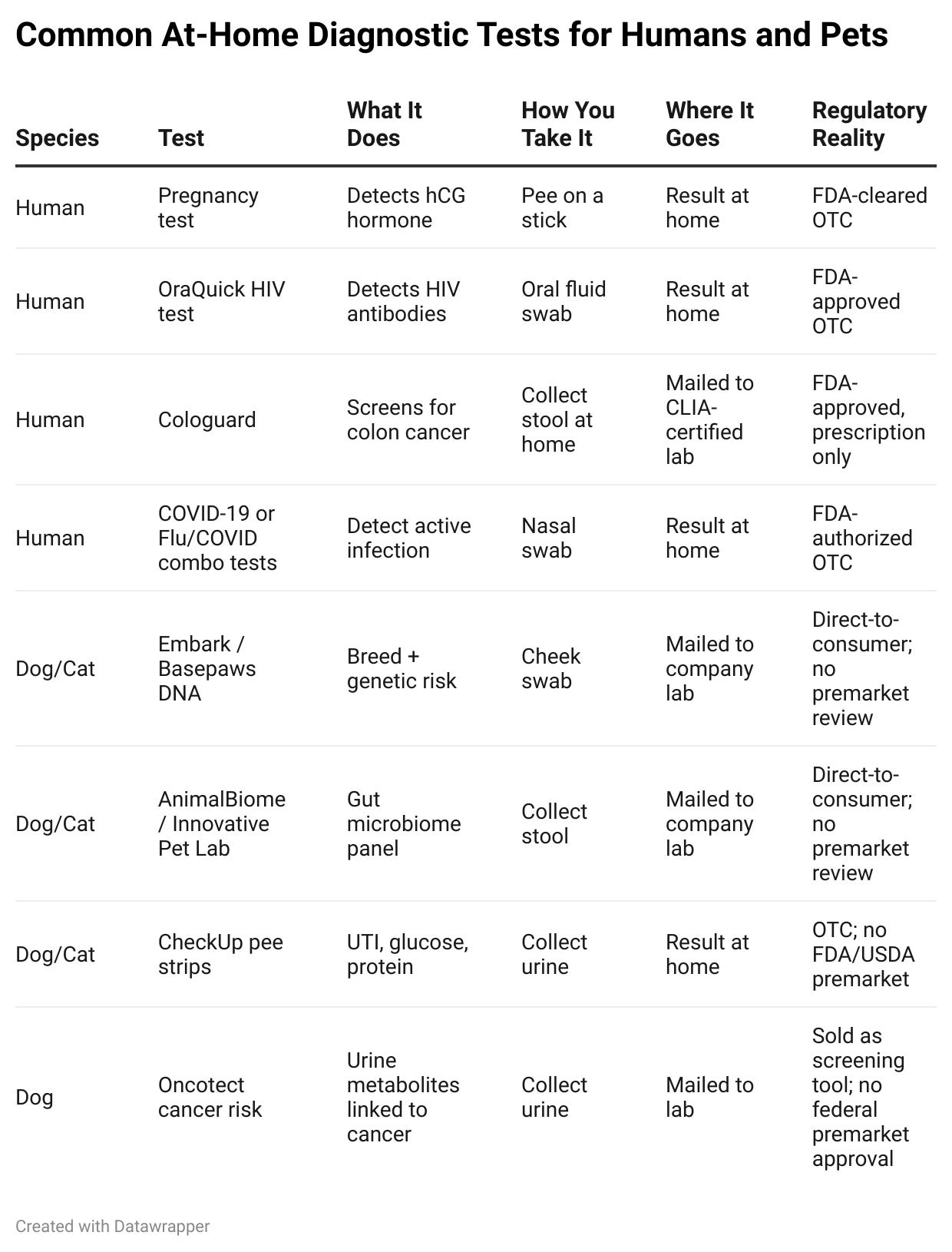

As previously mentioned, there are really two kinds of “home” diagnostics. There are the mail-in kits, where you collect a sample from yourself and send it to a lab. And then there are the true at-home tests, the ones you can run entirely on your own, with the results appearing right in front of you.

Both types exist in human health. Both types exist in pet health. But the way they are treated and regulated differ dramatically.

To illustrate this, I made a table below with some “at-home” tests that are currently available. All items are real and available for purchase today.

On paper, these tests look and feel almost identical. Cheek swabs, urine strips, stool cups, mailers, and lab results – the mechanics are the same.

But their pathway to market? They may as well be operating in different universes.

In human medicine:

Mail-in tests must use Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified labs.

Purely “at-home” tests must pass FDA review.

Claims must be validated.

Accuracy must be demonstrated.

Humans do have a small “wellness loophole” (think ancestry kits, microbiome tests, and “hormone insights” ). But even those tests still operate inside a regulatory exoskeleton: CLIA labs, FTC rules, and FDA guardrails if they wander too close to disease claims.

There is always a floor.

In pet medicine:

Do labs meet CLIA standards? No. There is no equivalent.

Premarket review required? Often not.

Accuracy standards? Nope.

Inspection schedules? Not mandated.

Avoid disease claims? Avoid regulation entirely.

If a company calls its test “screening,” “wellness,” or “health insights,” it can sell direct-to-consumer with no federal pre-approval.

Again, the tests look similar on the shelf. The rules, the oversight, and the stakes do not.

My curiosity once again kicked in. Why do these two ecosystems look so similar on the shelf and so different behind the scenes?

No CLIA for Cats

Now that we’ve established what an “at-home” test encompasses, let’s chat about the regulatory ecosystems at play.

In human medicine, the labs that process mail-in tests must adhere to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). CLIA governs accuracy, inspection schedules, and quality controls. Its job is to establish quality standards for laboratories performing testing on human specimens (saliva, blood, urine, etc.).

And the tests sold over the counter, the ones you run yourself, must first be reviewed and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Companies are required to prove that the device works, that ordinary people can use it correctly, and that the results are reliable.

Regulations exist with the intent to provide humans with validated, safe, and effective medical tests. There’s also a large body of literature documenting the barriers that regulation creates. My favorite recent post by Adam did a deep dive into why clinical trials are so inefficient. Dr. Parker Rogers (previously covered by Marginal Revolution, but a newer paper version exists here) finds that deregulation of medical devices (the category that includes at-home medical tests) can increase the quantity and quality of new technologies. Rogers’ paper measures the outcomes of FDA-regulated devices switching “classes” or being downregulated/deregulated.

There’s no way to parallel Rogers’ work in the animal health space. Simply because there is no FDA device classification system for animal diagnostics (e.g., animal take-home tests). Therefore, there is no device classification regime and no outcomes of deregulation to measure.

The aforementioned at-home pet tests, the allergy kits, the breed tests, and the microbiome panels did not go through the same gauntlet of FDA review that human tests face. There is a caveat to this. Testing that diagnoses or treats a disease goes through the USDA’s Center for Veterinary Biologics (CVB). These products may have additional regulatory hurdles, but still face a much easier path to becoming a commercially viable product. Additionally, the FDA does oversee animal devices; however, it does not require a premarket submission like in human medicine. The focus of the FDA in this instance is catching misbranding or adulteration of the product post-market entry.

Many popular pet “wellness” tests (genetics, microbiome, some rapid tests) simply avoid both FDA device clearance and USDA CVB by steering clear of disease-diagnosis claims.

As long as companies avoid making explicit claims that their tests diagnose or treat a disease, they can sell directly to consumers. They position themselves as a “screening tool.” An example of this type of product is Oncotect. Oncotect is an at-home, urine-based multi-cancer screening test for dogs. It assesses the presence of cancer-associated volatile metabolites in urine. Pet owners simply collect a urine sample, ship it, and for under $100, receive a result indicating if the dog is at low, moderate, or high risk of cancer. This finding can then be communicated to a veterinarian.

A Different Type of “Pup” Cup

As previously mentioned, Oncotect relies on a urine sample (hence “pup cup”) shipped to the lab. At this moment, Oncotect claims to be able to reliably detect cancers such as mast cell tumors, hemangiosarcoma, lymphoma, and melanoma. For those scientifically minded folks in the audience, their initial findings can be found in this 2022 paper here.

Oncotect claims “83% sensitivity and 96% specificity” for four major canine cancers, which sounds impressively high. Until you translate it into actual false positives. Cancer prevalence in the general dog population is only a couple of percent. So even with 96% specificity, roughly 4% of healthy dogs will still test positive. In a simple 1,000-dog example, that means about 17 true positives… and roughly 39 false positives. In other words, close to 70% of the “positive” results are false alarms.

I’ll be the first to admit “NOT GREAT.” Especially if you dig into the Frontiers paper and look at how small the sample of dogs was. This ain’t no gold standard randomized control trial (RCT) here.

In human medicine, my friend Hiya Jain wrote a great piece about early cancer diagnostics. She talks about Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) (what Oncotect is positioning itself as) and hails the progress that GRAIL has made on this front. She talks about GRAIL’s Galleri test, which is being evaluated in a 140,000-person NHS trial. In GRAIL’s 2020 validation paper, the test has an overall sensitivity of about 55 percent, with only 18 percent sensitivity at stage I, but a false positive rate of just 0.7 percent. As Hiya notes, the test has still come under extreme scrutiny despite being a milestone breakthrough in cancer screening.

So if GRAIL, with 0.7% false positives and a six-figure sample, is controversial, it’s fair to ask: why on earth would a pet owner use a test where most positive results are likely to be false? And why is a product like this even making it to market?

The Animal Health Market is Built Different

From an economics perspective, the answer is actually pretty straightforward. It’s not that dog owners suddenly have a higher tolerance for false positives. It’s that the structure of the animal-health market pushes companies toward this kind of product.

Pet insurance penetration in the United States is low. The North American Pet Health Insurance Association reports that in 2024, approximately 6.4 million pets were insured (their totals focus on cats and dogs). The AVMA recently reported there are approximately 88.7 million dogs in the U.S. and 76.3 million cats in the U.S. (~165 million pets total, so approximately 3.9% of pets are covered by insurance.) Most pet parents pay out of pocket at the veterinarian.

At this moment, very little data exists about the cost of veterinary care in the United States. However, as someone who has seen her share of veterinary bills, on an itemized invoice, the appointment fee alone at a veterinary visit will probably be between $60-$120 (depending on where you live). Add diagnostics such as bloodwork, imaging, cytology, and the bill climbs quickly. If you have an animal with a chronic condition, that isn’t a one-off expense; it’s a recurring line item in the household budget.

Now layer the test economics on top. An at-home cancer screen priced under $100 that you run once, on your own schedule, starts to look like a relatively predictable expenditure—especially compared to an open-ended in-clinic diagnostic workup. This doesn’t mean the test is “cheap” in any absolute sense, but it does make the cost structure more transparent from the owner’s point of view. You know the price up front, you can decide whether you’re willing to pay it, and you can defer or repeat it without navigating clinic capacity or appointment availability.

While products like Oncotect may be far from perfect, you can start to see the allure. Especially if there is market demand for such a product, one would imagine that the testing capacities will only get cheaper and more accurate.

High-quality testing has actually appeared in segments of the animal health market. Well-known labs such as IDEXX voluntarily comply with human-grade standards. IDEXX provides many of the standard labs and blood panels your pet receives when they come in for an annual checkup. They are the gold standard in animal health. As Gen X and Millennials continue to spend more on their fluffy friends, companies like IDEXX understand the desire for pet owners to have access to medical services on par with those found in human health. Markets at work!

Another major piece of this puzzle is simply money. The animal-health investment ecosystem is much smaller in comparison to human biotech. Additionally, there are fewer grant dollars and a dramatically smaller pool of possible acquirers for startups that make it to exit. Major players in animal health include Zoetis, Elanco, Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, and Covetrus. With the partial exception of Boehringer Ingelheim, these companies do not sit inside large human-biotech conglomerates. There is no obvious pathway for animal-first diagnostics to “graduate” into human medicine.

Small markets with few exit paths naturally push innovators toward products that can:

launch quickly,

avoid regulatory purgatory,

and generate revenue early.

Which is exactly the incentive environment that produces things like a $99 “pup-cup” cancer screen with high false positives but very low regulatory friction

Even with lighter regulation, the spillovers in this space overwhelmingly run from human diagnostics to animal diagnostics. Humans get the RCTs, the massive trials, the billions in capital, and the FDA review pipeline. Pets are more likely to get the leftovers. Whatever can be miniaturized or simplified for consumer use.

That’s why products like Oncotect exist at all: not because animal health is leading the frontier, but because dogs can be an easier commercialization environment for ideas that would require years and tens of millions of dollars to validate in humans.

There have been some animal health companies openly talking about trying to reverse this trend. Loyal, a longevity company in the pet space, has expressed interest in eventually crossing into human aging therapeutics. Loyal recently obtained an expanded conditional approval from the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine for one of its dog-aging drugs. (Unlike the take-home tests, animal drugs still need FDA approval.) Pet drug development is under FDA jurisdiction, but under a different (and generally more flexible) set of conditions than human drugs. Trevor Klee wrote a Works in Progress piece about these differences and talks more about Loyal there. It remains to be seen if “pets first, then humans” will work in practice.

Where This Leaves Us (for Now)

The at-home pet diagnostics world is messy and under-regulated in comparison to its human counterpart. It’s also absolutely exploding. It sits in a weird corner of the economy where consumer demand is rising fast, regulation is almost nonexistent, capital is scarce, and the technology frontier is mostly borrowed from humans.

Some of this is good. Some of it is probably bad. A lot of it is simply unstudied.

I’m not ready to declare whether this ecosystem is a policy failure, a victory for those concerned with regulation and its impact on innovations, or something in between. What I can say is that this space raises a long list of questions I’m still trying to understand, including:

Questions I’m still thinking about:

What does this do to clinic workflows?

Does bypassing the VCPR strengthen or weaken the veterinary profession?

Due to low regulations, is the animal health space innovating faster than the human health space?

Will the low-regulation environment attract more moonshots, or more junk?

Is this a stepping stone toward something bigger (like Loyal hopes), or a permanent niche?

And long term: which of these products actually improve outcomes for animals?

This is a young market. It’s moving quickly. And no one is really tracking what happens next.

So that’s where I’ll leave it for today — a map of the landscape, not a verdict. And in future posts, I want to dig into the knock-on effects for veterinarians, for the VCPR, for innovation speed, and for the future of animal health.

Because we are very early in understanding what a world of at-home pet diagnostics looks like. And even earlier in understanding what it means.

A very lengthy post to say I received a fellowship at Ani.VC! I am excited to learn more about the animal health space and cannot wait to keep writing on it.

Many thanks to Hiya Jain, Venkatesh V Ranjan, Adam , Grant Mulligan, and Julius Simonelli for feedback on various draft versions! I cannot overstate the importance of being surrounded by good people, and I am thankful that The Roots of Progress fellowship has brought many of them into my life

A great read on an emerging space. Thanks for sharing.

1) This was a fascinating overview!

2) Congratulations on your VC fellowship!!

3) As a consumer, beyond the Embark DNA testing kit, were there any tests you felt compelled to try for your own pups? (Asking for potential Christmas gift ideas!)